When the priest said the last rites over my unresponsive dad in hospice Thursday, I was startled to hear this line from John 14:2 … My father’s house has many rooms.

I was also startled to hear the priest call him James when his name was Robert. I’m probably going to hell for interrupting a priest mid-prayer, but I couldn’t bear the thought of Dad finally getting to heaven only to be sent back on a technicality. Not on my watch, baby.

Dad had been in the hospital for a couple of weeks after a fall. He was refusing treatment and only wanted to be made comfortable as he died. We knew the end was near for him. We also knew that’s exactly what he wanted.

I went to see him in his early days of hospice, about an hour away from me. After the first visit, I drove across Colorado Springs toward his house. I wanted to visit there one last time before we had to start making changes, cleaning, sorting, disrupting, erasing it of its Dadness.

The trip from the hospital to his house took me right through my places of memory. After all, I was born in the hospital I’d just left. I could see the school I’d attended in 1st and 2nd grade through his hospice window.

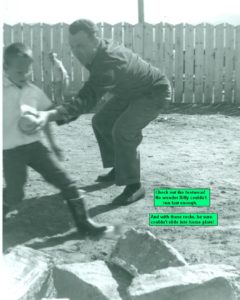

I drove past the tiny house with the huge tree in the front yard, only a stick when Dad bought it. I remembered all the games we played in the backyard; baseball, pickle, horseshoes, tag, hide and seek, and my favorite, Try Not To Fall In The Open, Uncovered Fire Pit. Dad was never a stickler for safety. As a parent myself, I’m horrified at all the times he gave me a hatchet when we were camping and let me whack logs while straddling them. It’s a miracle I still have ankles.

I drove through the neighborhood where we’d lived in two different houses, both of which we’d rented after returning from a few years of living in Casper, Wyoming. At one of them I was tasked with delivering the rent check to our landlords who lived a few doors down. I hated this job because I went to high school with the daughter. She was a senior to my sophomore, probably didn’t even know who I was, but I was so embarrassed by this duty. I got mad at my dad once, announcing that I wouldn’t do it anymore. He calmly took the check from me and delivered it himself, saying, “There’s nothing shameful in paying your bills.” I never made another fuss. Well, not about that.

I remembered his beloved dogs who’d leap up from a dead sleep when they heard his car about a mile away, waiting in the doorway, tails going 90mph, exploding with joy when he stepped into the house.

I wonder if Dad felt as I did, entering our houses. No matter what had happened that day, when I got home and closed the door behind me, I was safe. Nothing bad ever happened here. It was King’s X. Home free. I made it through another exhausting and drama-filled day of school and could finally remove my mask and let down my guard.

I thought about all the kitchen tables in all those houses, no matter how big, no matter how small, no matter the city. We gathered, eating simple but delicious home-cooked meals, and stayed long after our plates were empty, engrossed in long, lively conversations, often concocted by Dad. He’d lob random topics for discussion — cows are better than pigs for society … Shakespeare didn’t write those plays … there’s no good music anymore … women shouldn’t drive. As God is my witness, I was a full-grown adult before I realized he didn’t really believe cows were better than pigs or that women shouldn’t drive. It was just his way to get us to think, choose a position and defend it. He was a grand poobah Toastmaster from early on, and he gently forced those lessons on us. I went through a teenage phase where I could barely speak because when I did, he’d hold up fingers to count my “ums” or “y’knows.” Devastatingly effective.

I drove past the site of my first job, where Dad would pick me up after we closed at 9pm. I was learning to drive and he’d have me drive home. Once, I drove all the way without my lights on, Dad sitting calmly next to me, waiting for me to realize. When I pulled into the driveway, completely clueless, he said, “Pretty dark out. I wonder why they don’t make some sort of apparatus on cars that can light your way in the dark.”

I passed streets where so many of my friends lived, thinking about the countless times Dad picked me up when I called him to come get me. No questions asked. If I called, he was there. I wonder now if I ever really thanked him for all the times he did my bidding like that. Probably not.

He told me once that whenever he got those weird hang-up calls in the middle of the night, he always thought it was one of us needing him. Forget the fact we were all adults with families of our own. I’d laughed and said, “I live in Colorado. What would I need from you in Arizona in the middle of the night?” He shrugged. “I dunno. But I always answer.”

And he always did.

I hope he knew I was grateful for the little things as well as the big things. Those rides, those backyard games of pickle, those dinner conversations. Encouraging me to go to college when he didn’t understand the process or have the money. Being there for dinner every night. Knocking nurses out of his way to reach me when I was crying from the anesthetic at the oral surgeon, despite his lifelong fear of dentists. All he knew was that I was unhappy and he needed to make sure I was okay.

I can’t remember ever specifically saying thank you, but maybe I did in Father’s Day cards, or those long, long conversations we’d have when I went to visit him in Arizona after he retired. Or maybe he just knew, like fathers do.

My father’s house has many rooms.

I walked inside, assaulted by the cheap cigar aroma that permeated everything, right down to my mitochondria. After I die, and they’re doing an autopsy on me, the coroner and his assistant will have this conversation.

Coroner: Do you smell that? What is it?

Assistant: Grape flavored cigarillos.

Coroner: Grape?

Assistant: Yes. A tasty and unusual smoke. Sixty for the low, low price of $29.95. They were only sold to an old man in Colorado. He used them to torture his children.

Standing in the center of the living room, it was hard to realize he wouldn’t ever again sit in his recliner in the corner, dropping ashes into the plastic trashcan next to it. He was consistently nonplussed about setting it on fire, which happened more than once.

Dad lived in Prescott, AZ for many years, volunteering as a docent at the Phippen Art Museum, where he collected western art and schmoozed with the artists. It didn’t matter if the artists were famous or not; if he liked an artist’s style, he’d buy their art and champion them. On his walls hung all of his art, much of it in the living room. Forget thoughtful placement of these paintings — if there was space on his walls, it hung.

My father’s house has many rooms.

The kitchen. More art. His huge dry erase board where he noted Toastmaster meetings, outings with his friends and family, concert tickets. I noticed that even though it was March, it still showed October events, which broke my heart, this diminished life he was living. The corkboard held reminders for dentist and doctor appointments, long past, for which he most assuredly did not present himself. Cookbooks that he rarely cooked from but read as if they were the deepest, most moving literature. The big glass bowl in the center of his table, a repository for restaurant coupons and reviews clipped from the newspaper, notes to himself, and oddly, a large vintage photo of his father. Whenever anyone was visiting within spitting distance of lunch or dinner time, he’d fish out the coupons and ask, “Where are we going?” while calling out the names of restaurants and the deal they were offering.

This is where the cabinet fell off the wall one day, crashing down and spewing glasses, vases, and coffee cups all the way across the kitchen.

He told me about it on the phone one day.

Me: Wow, Dad. Good thing it was during the day instead of the middle of the night. What did you do?

Dad: Waited for the housecleaner to clean it up.

Me: He happened to be there?

Dad: No. Came on Friday.

Me: I thought you said this happened Tuesday.

Dad: Yeah.

Me:

Dad, annoyed: What?

I wandered into the spare room where I’d spent many a night visiting him. I passed his collection of horny toad art above the table where his gallon can of wood stain lived and thrived for at least three years. Maybe it was yet another art installation. If art is meant to make you ask questions, then it most certainly was.

I stuck my head into the guest bathroom to pay homage to his flock of shampoos from many years of his travels. God forbid you try and use one, though. No. Better to remain dirty-haired than to get The Look. *shudders just thinking about it*

The guest room also houses his record albums, cassette tapes, CDs, and DVDs. He has all the movies you’d expect an 88-year-old man to have, but also a big box set of “Friends” episodes. Go figure.

Dad loved musicals, and I suspect that’s why I do, too. I remember in about 1970 he took us to one of the big theaters in town to see the movie musical “Scrooge.” I still watch it every Christmas. The first stage show I saw was also courtesy of my dad. “1776” at the Air Force Academy. I was hooked.

Dad’s favorite show is “Phantom of the Opera” which is probably my least favorite show. So screechy. We argued about it constantly. But he told me how much he identified with the Phantom, always feeling a bit out-of-place. He told me how nervous he was around women in high school, which I found completely endearing. I also thought it was crazy, because I’ve seen him chat up everybody everywhere with an ease that would make George Clooney jealous. But it’s hard to shed those imprinted ideas of ourselves, I guess.

Dad went to Ireland a lot … A LOT … and it seemed he always ran into this one girl — Shirley at Bunratty Castle. They serve a medieval dinner there with madrigal singers and such, and he absolutely fell in love with her. I was with him on one of these trips and he pointed her out to me. I nudged him to go say hi to her and it might have been the one and only time I saw him blush. Two of my sisters traveled with him another time when his knees wouldn’t let him go up the stairs of the castle. They saw Shirley and she came down to say hello to my father. I’m sure it made him blush for three weeks straight.

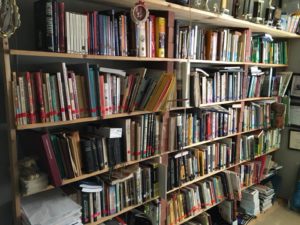

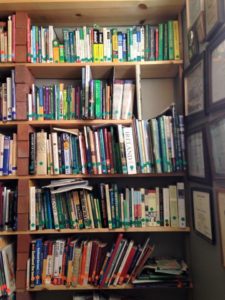

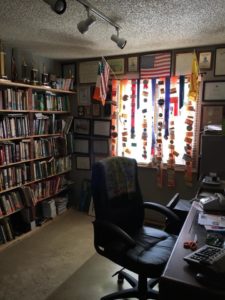

Pictures do not do his office justice. Dad had a lot of stuff, but he was organized about it. His books organized by colored sticker; all his Ireland (green) and Scotland (orange) travel books in one area, for instance, on shelves made of sturdy, practical, unadorned and unpretentious bricks and boards. His file cabinet jammed with his speeches and stories. His closet with Santa suits he donned for office parties and children’s organizations. His typewriter at the ready, much more friendly and useful than the computer whose only purpose was to infuriate him. Everywhere you look are trophies, awards and accolades from a life full of accomplishment and effort.

As western art covered the living and dining areas, family photos covered the walls of his bedroom. He loved his family fiercely, but privately. No gushing for him. Just the rock solid notion that we were his and he was ours.

Everywhere my glance landed around the house, I saw my dad. His personality, his desires, his accomplishments, and yes, his cigar seeped into every corner, every fiber, every surface.

My father’s house has many rooms.

I’m the 7th of 8 kids. Dad did his best to give us each our own rooms whenever possible in the various houses we lived in. Problem was, he wasn’t very handy. He created a warren of rickety, makeshift walls from cheap wood paneling in several basements I can remember. I suspect the subsequent owners of those houses dismantled everything before letting their own children inside, disposing of what they probably surmised was some sort of tenement hovel for ill-clad and ill-treated house elves. But no. It was just our bedrooms. Made by our Dad. Never with a door, though, because hinges are hard.

My father’s house has many rooms.

Grief is an interesting phenomenon. Dad’s death was not unexpected and not unwelcomed. He was tired of living. Everything hurt. Everything was difficult. His life had caved in on itself and he was done.

Despite this, I burst into great heaving sobs yesterday when I realized he’d never see the dedication to him in the new series of mysteries I was writing set in the world of crossword puzzles. I knew as soon as I had the idea that these would be dedicated to him, an avid cruciverbalist who didn’t believe a puzzle was solved until it was solved in ink. When I finally made the leap from pencil to pen, he never said so, but I’m sure I went up a couple of notches in his esteem.

But in the middle of these great heaving sobs I started to laugh because Dad would never have read my crossword puzzle mysteries anyway. “I don’t read fiction,” he’d say with a shrug.

When he was in the hospital, my siblings and I each tried to come up with two words to describe him. Mine were “stubborn and that-treat-that-has-the-hard-cookie-on-the-bottom-and-that-gooey-marshmallow-center-and-the-crunchy-chocolate-coating-on-top.”

Others were: grumpy, sentimental, Archie Bunker, hilarious, generous, gregarious, aloof, donkey-headed, puppy-hearted, hibernophile, bibliophile, affable loner.

His time in the hospital (his hospice was in the hospital, not at home) was frustrating for him. We kept telling him he could go, there was no unfinished business here, we loved him and he was free to go on his next adventure. One time he opened his eyes, glared at me and said, “Do you think I’m not trying?”

But as frustrating as it all was, he was still hilarious. My husband and son brought a bottle of very expensive whiskey, a recreation of a long-lost recipe, and glasses to share one final shot with him. He accepted his glass, looked my husband in the eye and said, “I’m DYING here and you bring me a BLEND??”

There’s got to be a better way to die, to honor these brave and marvelous people in our lives. Watching them fade away, often in pain, is not it.

Some people will disagree with me, believing that every minute on earth is precious, and that’s fine, but I am not one of them.

He was so excited when Colorado passed assisted suicide legislation, but he couldn’t take advantage of it. Apparently, untreated diabetes is not on the approved list of terminal illnesses. Go figure.

If Dad could have sat down with the legislators, I’m sure it wouldn’t have been long before they’d see things his way because he touched everyone he met. His housecleaner told me, “It was a pleasure and a blessing to have known him. I so enjoyed our conversations.” His travel agent said, “I fell for him right away. He was so unique and I appreciated him.” His hospice nurse told us she never cries on the job, but she cried over the loss of our dad.

I wish you could have met him. He’d have loved meeting you.

Goodbye, Dad

You were once my one companion

You were all that mattered

You were once a friend and father

Then my world was shattered

Wishing you were somehow here again

Wishing you were somehow near

Sometimes it seemed if I just dreamed

Somehow you would be here

Wishing I could hear your voice again

Knowing that I never would

Dreaming of you won’t help me to do

All that you dreamed I could

Passing bells and sculpted angels

Cold and monumental

Seem for you the wrong companions

You were warm and gentle

Too many years

Fighting back tears

Help me say goodbye

John 14:2

in domo Patris mei mansiones multae sunt si quo minus dixissem vobis quia vado parare vobis locum

in my Father’s house are many rooms; if it were not so I would have told you; for I go to prepare a place for you

30 thoughts on “My Father’s House Has Many Rooms”

This is a beautiful tribute to your father. May he rest in peace.

Becky, this is the most beautiful eulogy I have ever read. So much of what you say about your father reminds me of mine (who went way, way too young at 62). I’m sending you love and hugs and what little cyber comfort I can. Thank you for sharing his life and your life together with the world.

Few things make me cry. This was one of them.

Oh Becky, this is such a lovely tribute. My condolences.

A simply beautiful tribute to a unique and inspiring man. Godspeed to your dad and a huge hug to you.

So beautiful and love filled. Thank you for sharing your dad with us. Hugs.

Beautiful tribute. I’m sorry he’s gone he sounds like a wonderful and generous man.

Bec you have me laughing my ass off and crying harder than I have in a while. Oh Sweetie…I could see every expression you describe through your words which reflect your heart! I could see my Daddy really running to meet your dad …Yet my mom was more like your dad and I could see her standing with your mom even though they never met saying it is about time you got here.

I just repurchased two of your books I was not able to read before my niece stoled and I ordered the new ones. It was very important to me to do this when I got a small inheritance check a month ago. I will honor you and your amazing unique soul of a DAD by reading, yes I will read fiction. God Bless you my friend the days ahead wont be easy but remember he is out of pain! Love you Meg

Dear Becky: I can barely believe that I was online with you yesterday and had no clue about the loss of your father. Please accept my sincerest condolences for your loss of a man that I’m sure I would have truly enjoyed meeting had I ever had the chance! Your tribute to your father and your life is beautiful and touching. I was mesmerized!

May you recall many more wonderful and interesting memories and find comfort and joy from them. You definitely are an amazing daughter daughter and rest assured your Dad knows this and was very proud of you.

Sincerely Cynthia Blain

Absolutely beautiful, B. Much love to you and your family.

So beautiful, B. Much love to you and your family.

Such a lovely tribute to your father! Thank you for sharing your heartfelt love for him. My condolences to you and your family on your loss.

Dear Becky,

I will be thinking of you during this time of adjustment. Like you, I’m happy that your dad has made the last journey on his list at the end of a fully lived life, but, I know you will miss him painfully for awhile while you feel the separation. I know that you know that you are surrounded with memories, as well as family and friends to share them with. I thank you sincerely for sharing him with us. I feel his loss in the world. My heart is with you. ❤

Beautiful. Just beautiful. You had me crying and laughing all at the same time, damn you 🙂 R.I.P. Robert.

U HIT THE NAIL ON THE HEAD HERE… PEACE BE WITH U ALL.

I grieve with you. Know that your world of loss is shared. That you are loved, that one of your father’s rooms is in your heart. May you be well. May you find peace.

Lovely and elegant writing. You know I don’t say that often,.

A lovely piece of writing, Becky. You give me a great sense of your father. It’s hard to lose our parents even when it’s time. My condolences.

Uncle Bob is surely proud of you and all your siblings Becky. God’s Peace to you all.

Beautify written. I wish I had known him before……

Thank you for sharing

Pingback: High Highs and Low Lows – Mysteristas

Deb so sorry to hear of your Dad’s passing. You have been on my list to call. I feel bad I put it off. I just read your beautiful trubut. Your words are so descriptive of a wonderful father. We will get together soon.

Take care you and your family are in my prayers tonight. Sue

Pingback: The Life Blood of Fiction – Mysteristas

Pingback: The Art of Dying Well by Katy Butler | Becky Clark, Author

Beautifully written. (Finally able to read it. Most of it.)

Hi Becky,

I just re-read this for about the, maybe, 10th time. As if my emotions weren’t already right at the edge of tears (re the Covid-19 quarantine and Kendy and I being basically under house arrest), this writing brought me to tears again. Thanks so much!!

Hi Becky,

I have just re-read this for, maybe, the 10th time. As if my emotions weren’t already on edge (re. the Covid-19 quarantine where Kendel and I feel as if we’re on house arrest.), it put me to tears. Again. Thanks so much!!

Let me just point out, the real comment from me is this is very good writing.

Thanks, Steve. I appreciate that. You made me wonder how many times I’ve read this!

This is so beautifully written. He sounds like a wonderful person. Some things reminded me of my dad.

Thanks, Helen.